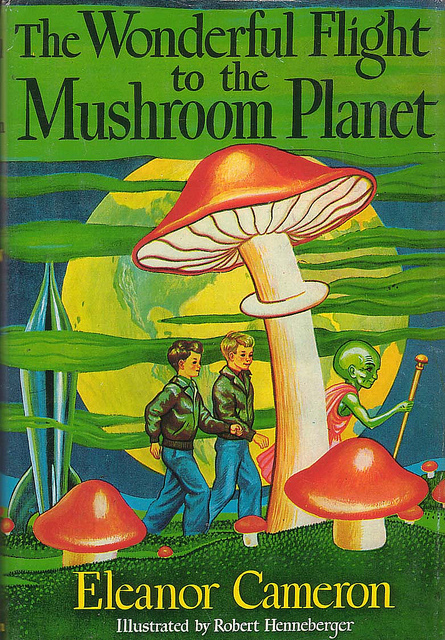

Young David Topman divides his time between reading and dreaming of travelling between planets in his completely imaginary spaceship. So, when a newspaper ad directly asks for a small spaceship built by two boys (I’m quoting, before you all start protesting) promising adventure to the boys delivering said ship, David immediately leaps at the chance.

He enlists the help of his friend Chuck, and with some scrap metal and other household products, they manage to put together a little spaceship—one that might just be able to make Eleanor Cameron’s The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet.

As it turns out, the ad has been placed by Mr. Bass, a most peculiar little man. Quite excitable, he has invented scores of things, including a special sort of telescope that has allowed him to spot a very tiny planet about 50,000 miles away from Earth, which, in an elaborate pun, he has named Basidium. And, as it turns out, he isn’t exactly human, despite his humanoid appearance. Rather, he is one of the Mushroom People from that planet. The boys, I must say, take this proof of extraterrestrial life very calmly. They’ve either been reading too much science fiction, or not enough.

Mr. Bass wants boys to lead a scientific expedition to Basidium—on the basis that any residents of this planet would be terrified by adults, but not of children. (If you are wondering how on earth the planet’s residents, who apparently know nothing, zilch, nothing about humanity, would be able to tell the difference, I can only say, handwave, handwave, handwave.) So, with some quick improvements to the ship, some very careful calculations of the necessary speed and orbit, and a quick stop to pick up a chicken for a mascot (her name is Mrs. Pennyfeather) they are off to the Mushroom Planet.

Here’s where the book gets interesting, on two different levels.

Eleanor Cameron published The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet in 1954—three years before Sputnik, when orbiting the earth was still in the realm of theory and possibility, not reality, before anyone took pictures of the Earth and the Milky Way from orbit or from the Moon. This both hampered and freed her imagination. She knew enough to make some very accurate guesses about the effects of earthshine both on her kid pilots and on the mushroom planet, and enough to make some slightly less accurate guesses about the appearance of the sun and stars. It’s an intriguing glimpse of imagination just before spaceflight.

Even more interesting is what happens once David and Chuck arrive at the Mushroom Planet. Things are, to put it mildly, not going well there: the ecology is collapsing, and the magic plants the Mushroom people use to stay healthy and green (Cameron’s description, not mine) are dying. My sense is that Cameron did not put a lot of thought into the culture, ecology, or life cycle of the Mushroom People; nonetheless, in a few quick sentences, she shows a culture that does not think quite the same way, a culture that never considers experimentation or a focus on science, for instance.

The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet, however, does love experimentation and science, so, not surprisingly, in two short hours David and Chuck are able to save the Mushroom people through observation, deduction, and knowing something about sulfur.

But right after saving the Mushroom people with Science, David and Chuck immediately decide that they have to save the Mushroom people from Science: that is, they cannot and will not tell U.S. scientists and other interested observers (but mostly U.S.) about the Mushroom People. Announcing this discovery, they decide, will lead to several scientific expeditions to the Mushroom Planet, which will inevitably disrupt the lives and culture of the Mushroom people. For their own protection, the Mushroom Planet must be kept secret.

This is straight out of pulp fiction, of course, and it feels rather paternalistic, even coming from two kids. After all, no one asks the Mushroom People how they feel about potential scientific expeditions. Given that they very nearly died from something easy to prevent—and that several potential cures exist on Earth—I could even see arguing that keeping the Mushroom People secret means dooming them to extinction.

And, although I cannot blame Cameron for not foreseeing this, I couldn’t help but think that although at 50,000 miles above the earth, the Mushroom Planet should be free from the risk of accidental crashes from satellites, it should also be relatively easy to spot from the space shuttle or the International Space Station with any of a number of scientific instruments, not to mention any accidental crossing of the visual path of the Hubble Telescope, so the kids are really only buying the Mushroom Planet a few decades. And, now that I think about it, I’m not going to give Cameron a pass for not seeing this: she lived in an era where people were widely speculating that space travel would be common—so common she could even imagine that two kids would be able to build a spaceship capable of leaving Earth’s orbit.

On the other hand, this is also a nice acknowledgement, less than a decade after the end of World War II, that sometimes, plunging into the lives and countries of other people is not always a good thing, even if the effort is led by American scientists. And I can’t help feeling a secret gladness that the Mushroom Planet will be able to live in peace—at least until the launch of space shuttle Columbia, and whatever is replacing the space shuttle program.

But although the book takes these and other science elements fairly seriously—there’s a good, solid explanation of just why a rocket needs to go so quickly to get off the planet’s surface—I can’t quite describe it as entirely science fiction, either. Far too many elements smack of just a touch of magic and whimsy: the way things just happen to work out, the way they mostly work out because David always remembers that he needs to have faith that things will work out. (In this, at least, the book shares some thematic consistencies with The Little White Horse.) Their mission is slightly more quest than scientific exploration, and Mr. Bass functions more as the wise old wizard mentor, or even a fairy, than the mad inventor he initially seems to be.

I don’t know if contemporary kids will go for this book or not—my best guess is maybe. Portions of the book—parts of the science, the way the invitation is issued to only boys, not girls, the various expressions used by the boys that would have seemed dated in The Andy Griffith Show—have not necessarily aged well. On the other hand, the book is pretty much non stop movement and action, and its hopeful message that kids really can change their destinies—and an entire world—is a reassuring one. And I’m definitely delighted with any book with the theme “Scientific knowledge saves lives.”

But if contemporary kids may or may not enjoy the book, kids reading the book in the 1950s loved it—to the point where Cameron, like many of the authors we’ve discussed here, found herself somewhat unwillingly writing a series, covered in the next post.

Mari Ness currently lives in central Florida, where she can sometimes catch a glimpse of rockets heading up into the sky.